Pele's spectacular career is filled with logic-defying feats that are unlikely to ever be repeated. No other player can boast three World Cup wins. Or 1,000 goals scored at the top level – although this fact is subject to endless dispute and discussion.

Nonetheless, the Brazilian legend, who died on Thursday, reached heights to which few of his peers, past or present, could ever even aspire. But there is one particular achievement that has persisted in popular myth for over 50 years and still has so many football historians asking themselves: Did O Rei actually help to bring peace to two warring nations?

This dramatic tale dates back to 1969 and one of Santos' famous globe-trotting tours.

Pele, Pepe, Coutinho and the rest of the club's Santasticos dominated South American football during the first half of the decade, winning five straight Brazilian championships, the Copa Libertadores twice and two Intercontinental Cups over European heavyweights Benfica and AC Milan in that glittering period.

From 1966 onwards, however, continental and even domestic glory took a back-seat for the Peixe.

Next Match

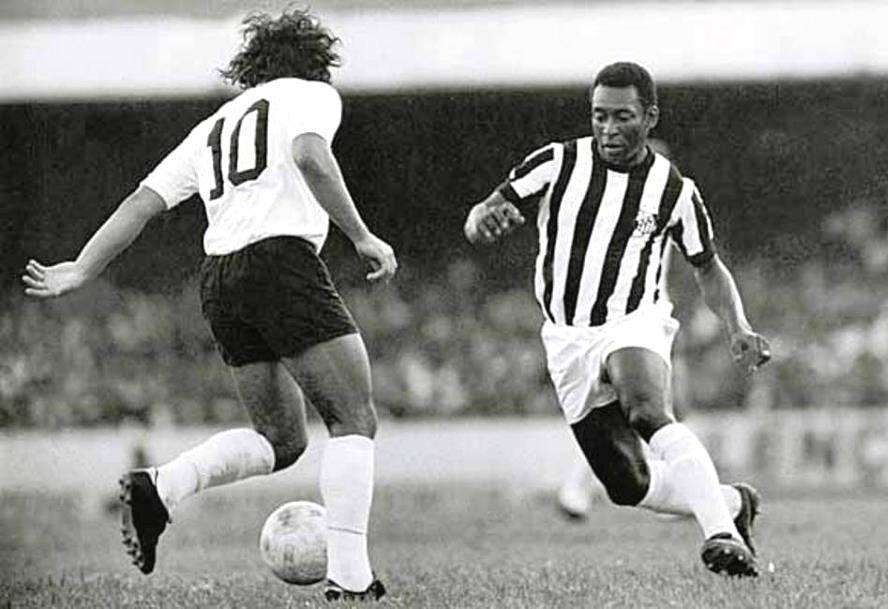

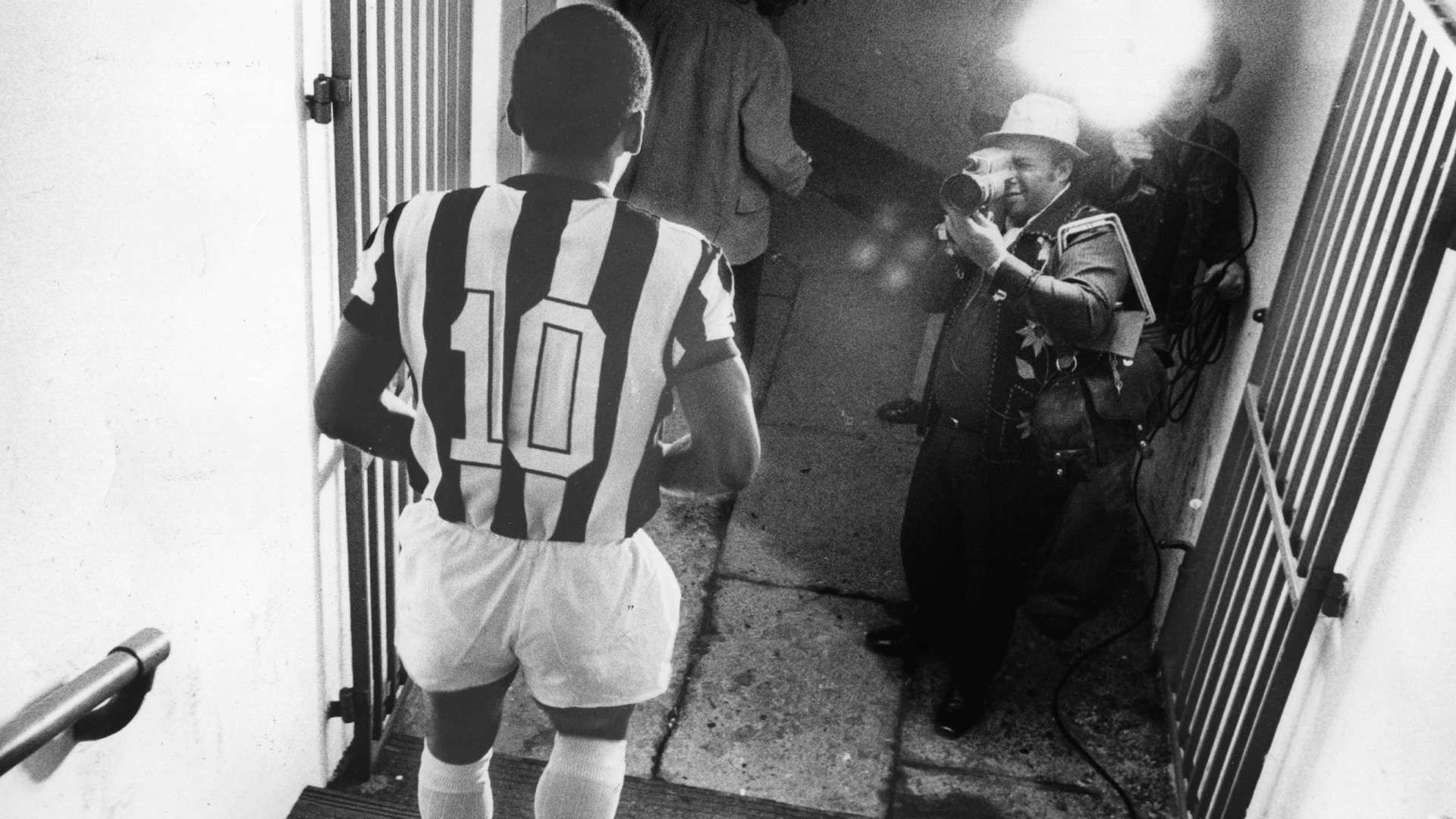

With Pele as their star attraction, the club began pulling out of the Libertadores in order to travel the world, embarking upon tours of the United States (1966), sub-Saharan Africa, Italy and Germany (1967), and Argentina (1968), where they participated in a pentagonal tournament in Boca Juniors' Bombonera that also included Benfica, River Plate and Uruguay's Nacional.

Almost nothing and nowhere was off-limits for Santos in their efforts to squeeze every cent out of their star-studded side.

One European tour in 1959 took in 15 games in nine different countries in just 22 days. According to Pele in Andres Campomar's book Golazo!, the following year was even more punishing.

“I remember counting that I had played 109 times for Santos alone in 1960," he claimed. "There was no break in the year's football.”

anotando fútbol

anotando fútbol Getty

GettyThey were aided and abetted by the Brazilian government, which in 1961 passed a bill declaring Pele a national treasure, forbidding his sale to a foreign club, thus leaving him at the mercy of Santos' gruelling tours.

The beginning of 1969, then, saw the Peixe heading to Africa with Pele in tow once more, even though the continent was in the throes of bloody upheaval.

A brutal conflict had broken out two years earlier between Nigeria and a secessionist state, Biafra, a civil war based upon the wishes of the Igbo people to break away from the central government dominated by the Hausa-Fulani group from the north of the country.

Over two years of bitter, internecine violence, an estimated two million civilians lost their lives and up to 4.5m were displaced from their homes, before Biafra was eventually overrun and reintegrated into Nigeria.

Santos arrived right in the middle of the war, ready to play a match in Lagos on January 26. However, according to the legend, when Pele & Co. rolled into town, the guns fell silent.

For 48 hours, Nigeria and Biafra held a ceasefire, during which Santos drew 2-2 with the Super Eagles, with Pele scoring both goals and receiving a standing ovation from the home fans.

However, other accounts claim that the cessation of hostilities actually occurred two weeks later in Benin City, on the border with Biafra.

Santos' official website insists that the region's military governor Samuel Ogbemudia decreed a local holiday and opened up the bridge that connected Benin with Biafra so that both sides of the divide could witness Santos' 2-1 victory over Nigeria in front of a crowd of 25,000 spectators.

According to Pele's team-mates Gilmar and Coutinho, the ceasefire barely lasted for the duration of the game; as the side's plane took off, they could hear from inside the craft the sound of gunshots that marked the resumption of conflict.

“Having stopped a war was one more point in our favour to show our supremacy,” fellow Peixe legend Lima recalled to Gazeta Esportiva.

“We could have easily turned around and said, 'War is all around us – why would we enter that mess?' But we didn't. We wanted to do it and we said: 'We are not obliged to play, but we want to and we are going to do this.'”

The story reached Time in 2005, with an article from the famous magazine claiming that “Although diplomats and emissaries had tried in vain for two years to stop the fighting in what was then Africa's bloodiest civil war, the 1969 arrival in Nigeria of Brazilian soccer legend Pele brought a three-day ceasefire.”

Thanks to the efforts of Nigerian blogger Oloajo Aiyegbayo, however, new doubts have arisen over the truth behind Pele's peace-making efforts.

Aiyegbayo trawled contemporary newspaper accounts of the period and found no mention of a ceasefire covering the period of Santos' stay in Nigeria.

The Benin City bridge may have been opened, but this was standard practice on match-days and not a measure designed to allow Biafrans into the stadium during a time when tensions were running extremely high due to a series of recent atrocities.

Pele himself has given mixed recollections of the event, stating in his autobiography only that “the Nigerians certainly made sure the Biafrans wouldn’t invade Lagos while we were there.”

In subsequent interviews, however, O Rei has accepted the more romantic retelling of the story as fact.

Fifty years after Santos' hectic, interminable tours, it is perhaps only natural that the former forward's memories of specific matches and countries might be less than impeccable. It is even possible that the ceasefire in question belongs to a different country and year altogether.

In 1967, the Brazilians had also found themselves in a war-torn corner of Africa, playing in both the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kinshasa, and in Libreville, Gabon.

In 2012, Pele returned to Gabon and regaled his audience with the part he played in halting a civil war that was ravaging the country. “They told us we couldn't go, there was a war on and we were crazy,” he explained.

“We played here [in Libreville] and also in Kinshasa, the father of [Gabon president Ali Bongo] was president then and he said: 'We have to stop the war because we are all going to watch Pele'. They stopped, we played and we left, it was fantastic. I cannot forget it.'"

Half a century after the facts, we may never fully know the truth behind Santos' famous tours: whether they were humanitarian missions as well as money-making exercises.

Or if the stories of stopped wars and peace-making are later inventions aimed at justifying what appears to our modern eyes to have been outrageous exploitation of young, talented footballers.

As with those 1000 goals – most of them unseen and shrouded in the darkness of an age when coverage was sporadic at best – it's really up to the reader to decide what to believe.