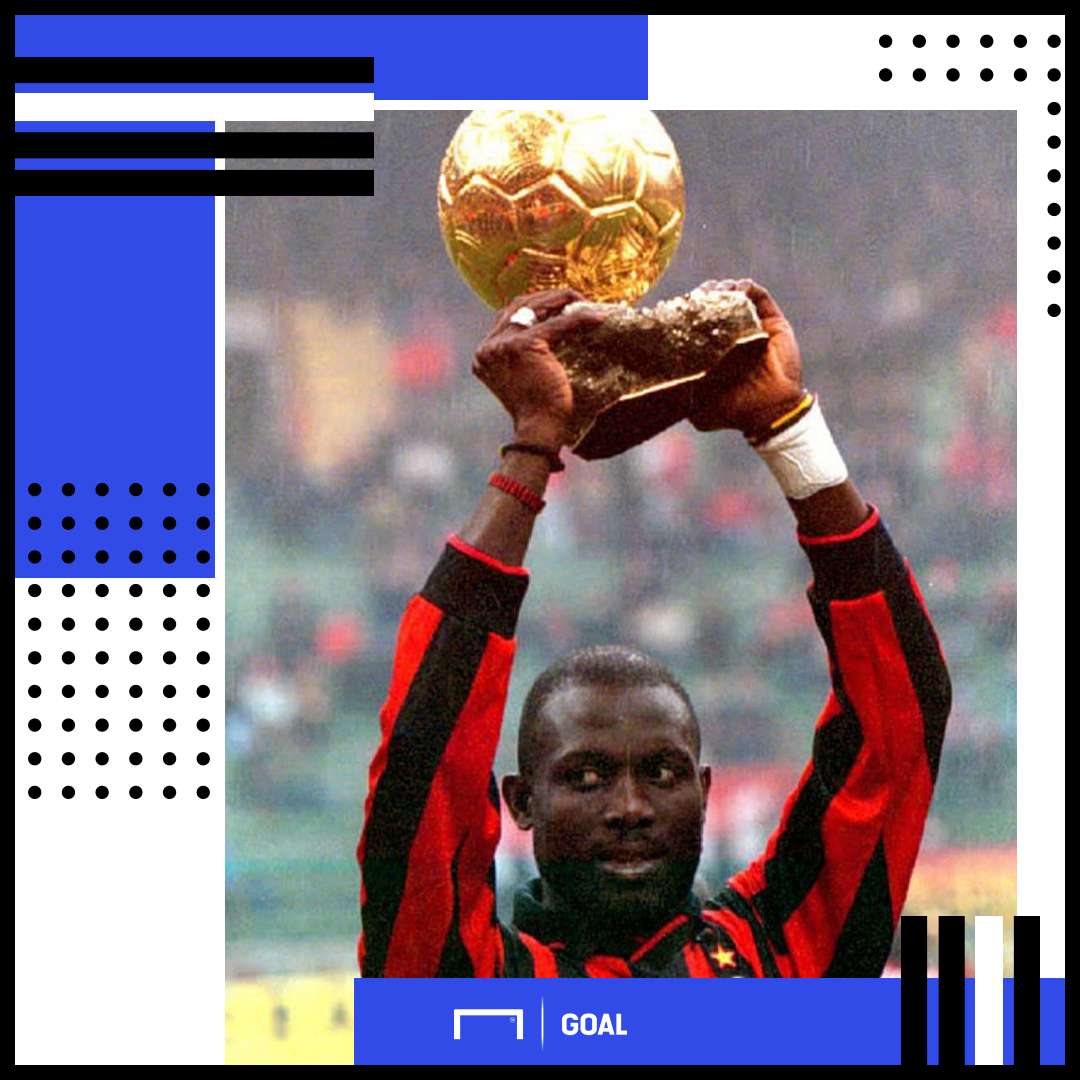

George Weah remains Africa’s only Ballon d’Or winner.

Of the current African crop, Mohamed Salah is the best bet to follow in his footsteps someday and – perhaps – is the closest thing we have to Weah himself. Like Weah, Salah was born, bred and developed within African football borders before moving to Europe. That is an increasingly rare pathway for young African prospects to follow.

He is joined in that regard by fellow Red Sadio Mane, who came through the prestigious Generation Foot academy in his homeland of Senegal before being picked up by Metz and later Red Bull Salzburg.

The Red Bull football group is doing good developmental work in that regard, with another Liverpool African Naby Keita having come through their ranks. Current Salzburg stars Diadie Sammesekou and Amadou Haidara might well feature on individual lists of the future once they move on and mature.

Beyond Liverpool, though, and the picture is troubling for those hoping to see Africans on the world’s best footballers' list.

There is a handful of forwards worthy of consideration – led by Ivory Coast's Wilfried Zaha. He may have been born in Abidjan but owes every bit of his progress as a footballer to life in England, the place where his family moved while he was still very young.

He even featured for England youth and for the first team in a non-competitive capacity. Indeed, had the FA been better prepared to recognise his talents then he would be a fully-fledged England international by now.

That story is similar to other African-born talents like Jean Philippe-Gbamin, born in Ivory Coast but who played for France at youth level, and Alex Iwobi, Lagos-born but an English underage player all the way up to under-19.

Meanwhile, Wilfred Ndidi, Thomas Partey, Jean Seri and Victor Wanyama might well be fine technical midfielders who play at a high level, but none are playing in the glamour roles for their clubs or countries and none are the class of Yaya Toure, who has gone before them.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

The challenges of promoting high-level African talent to Europe remains fraught with difficulty. Prestigious academies like the ASEC Mimosas one in Abidjan are suffering because of the competition provided by other youth teams in the territory who may not have the expertise or sense of pastoral care required to nurture talents to the highest levels.

And, increasingly, clubs and agents are opting to send players to teams on the fringes of things in Europe, where they lose their way, lose those crucial educative years and slip behind their peers.

In the case of Salah, it took a crisis like the Port Said disaster and a cancellation of the Egyptian league for him to move on to Basel.

There are indeed many other top class African internationals who owe their football careers to a lifetime lived in Europe. The likes of Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang, Riyad Mahrez and Kalidou Koulibaly lead this particular group.

All three were born and raised in France but opted for one reason or another to play for their countries on the African continent. It’s always going to be difficult to stand out for a team who rarely gets success on the global stage – another key point. It’s at the crucial stages of World Cups and European Championships that reputations are made. And no African team has ever qualified for a World Cup semi-final, so standing out is difficult.

In this group of European-born African players there are few more solid performers. Keita Balde, Hakim Ziyech, Yacine Brahimi and Cedric Bakambu are among them but the reality is – for many of this group – that if they were good enough to play for Spain, Netherlands or France as the case may be, then they might well have done so.

That’s certainly the case for some of the world’s best players, who might well be African-derived but are European by birth, upbringing and education.

Kylian Mbappe, Paul Pogba, Ousmane Dembele, N’Golo Kante, Samuel Umtiti, Nabil Fekir, Corentin Tolisso, Benjamin Mendy, Presnel Kimpembe, Steven Nzonzi, Blaise Matuidi, Djibril Sidibe, Adil Rami and Steve Mandanda all had the eligibility to play for one African country or another but are French.

In the case of France, there are more in that category coming up. Tanguy Ndombele is a star of the future and fellow Lyon man Houssem Aouar is also a France international-in-waiting.

Then there are Dayot Upamecano, Karim Benzema, Tiemoue Bakayoko, Wissam Ben Yedder, Alassane Plea, Abdou Diallo, Issa Diop, Mousa Dembele, Kurt Zouma, Moussa Sissoko, Mouctar Diakhaby, Malang Sarr and more to consider. All are French by birth, most are already capped and none has ties to Africa in a professional sense.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

That’s just to use the example of France. The same is true in other countries too where Dele Alli, Romelu Lukaku, Leroy Sane, David Alaba, Memphis Depay, Jonathan Tah, Michy Batshuayi, Antonio Rudiger, Jerome Boateng, Manuel Akanji, Inaki Williams, Tilo Kehrer and Serge Gnabry are all of African ancestry. They might have opted for those African countries for whom they are eligible had they not gone on to gain senior honours in Europe.

In any case, their football aptitude is a product of their environment and training, and not simply of their ethnicity.

Players are being produced more consistently in Europe than anywhere else, that’s currently beyond doubt. Where simply talent is in question, well, that’s another debate. There might well be talented kids all over the world – Africa included – but the systematic production of young players of all backgrounds and ethnicities in Europe puts it to the forefront.

Those French boys might well have picked up a football and been spotted had their parents or forefathers remained in Africa but it’s unlikely. Europe – and France in particular – gave them the chance to hone their skills in good academies, under professional-standard coaching and with the right advice and nutrition.

The academy teams of Ivory Coast's best and brightest might well match up to their European counterparts on the talent level but there is a clear divergence once things get serious.

A post-war explosion in immigration to Europe from north and sub-Saharan Africa has given us these national teams stocked with players from all kinds of backgrounds. That number is only going to increase in the next few years, with African nations accounting for eight of the 10 fastest growing immigration populations since 2010. That’s according to a recent report by the Pew Research Center.

At least one million sub-Saharan Africans have moved to Europe since 2010 with migration to the US also growing. Emigration from sub-Saharan nations grew by 50 per cent or more between 2010 and 2017. Conflict in places such as South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Burundi, DR Congo and Sudan has been a big driver, while many women and children are fleeing violence, disease and hunger.

In 2017, the Pew Research Center conducted a survey in South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Senegal and Tanzania – the six countries which have provided the highest number of migrants in Europe and the US – and four of every 10 respondents said they would move if they had the “means and opportunity” to do so.

The reasons cited were high unemployment, low wages, as well as political instability and conflict. And in those reasons, you can detect the back stories of many African-descended European football stars.

There are around 4.15 million sub-Saharan African migrants in Europe as of 2017, with the UK (1.27 million), France (980,000), Italy (370,000) and Portugal (360,000) leading the way. Africa’s population is projected to be 2.4 billion by 2050; it’s currently around 1.2 billion today and that has ballooned from 230 million in 1950.

It’s 23 years since the incumbent Liberian president picked up the top individual prize football has to offer and few Africans have come close in the meantime.

Samuel Eto’o and Didier Drogba are no doubt the best strikers produced by any African nation since Weah’s day but neither got on the podium throughout their careers.

Yaya Toure has been famously perplexed over the lack of African representation on the biggest individual stage. Despite his unhappiness, however, not one African player has made it into the final three since Weah.

Granted, this has been the era of Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi. Those two have dominated the race to such an extent over the last decade that every other player in the world is fighting only for third place.

Their stranglehold on the Golden Ball is now broken, though; the contest should be more open in the years to come. But don’t expect a new African contender to emerge from anywhere but Europe.