When the United States and France line up at Parc des Princes on Friday night in the World Cup quarter-finals, they will be evenly matched in almost every department.

Strong at the back, dangerous out wide and with experience and winning mentality running throughout the two sides, the two evenly-matched opponents are difficult to separate.

But there will be one glaring difference between the two when they take to the field.

While there are 12 women of color in Corinne Diacre’s squad, there are just five in Jill Ellis’s team - Crystal Dunn, Christen Press, Jessica McDonald, Mallory Pugh and Adriana Franch.

That is despite only 60.4 per cent of the U.S. being white, according to the United States Census Bureau, compared to an estimated 85% of France's population, per thinktank Institut Montaigne.

It’s an issue that Amir Lowery and Simon Landau have been raising and tackling for several years.

Lowery, a former MLS footballer for Colorado Rapids and Kansas City among others, began coaching after his retirement in Washington D.C. and realised the group at his first club "wasn’t representative at all of the city".

“It was almost 30 middle-class white kids. The inner-city kids, who are majority black or Latino, couldn’t afford it or weren’t getting those opportunities. They just weren’t in the picture,” he explains.

“I went out and started to look for kids to kind of shift the balance and in that process I met Simon, who was working with a local organisation here on a volunteer level called DC Scores.”

The pair are now in their fourth year of running Open Goal Project, an organization that aims to help ethnic minorities access and pay for these opportunities.

“Along the way, we’ve been peeling back the layers and discovering how much there is that affects the kids pursuing a youth soccer career and then connecting the dots up to the top level,” Lowery explains.

“It’s becoming obvious why it’s impossible for these kids to access high-level soccer and why the national team looks like it looks still and we’re almost in 2020.”

There is a complex web of issues, as Lowery explains. The cost of pay-to-play soccer in the US prices out lower-class families, many of those of an ethnic minority.

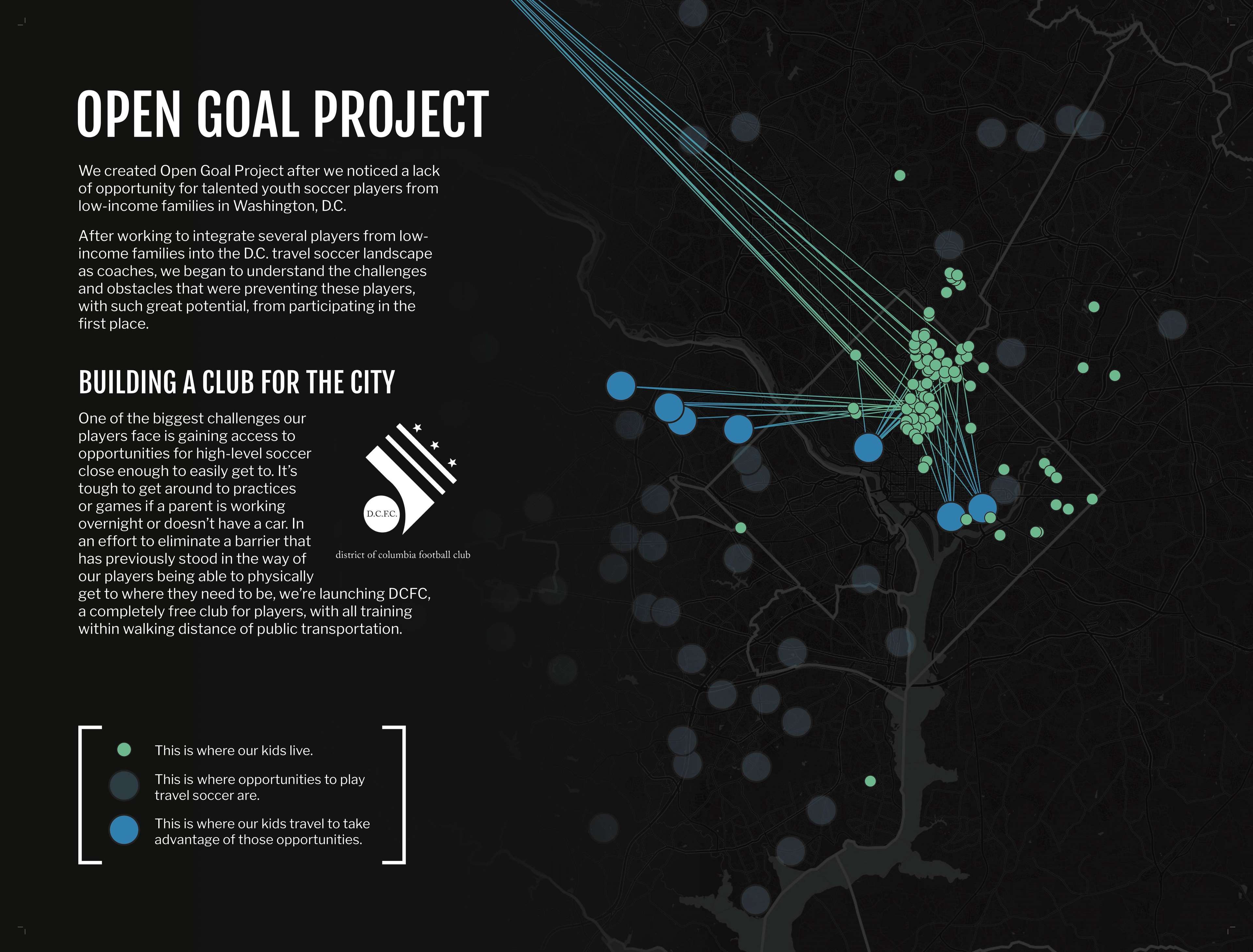

The accessibility of opportunities is not good enough, asking more money and travel from aspiring young footballers. Such opportunities to progress in the sport aren’t offered in lower-income communities.

Lowery believes U.S. Soccer, the governing body of the sport in the country, is the "main culprit" and has accused those within the organization of chasing profit over inclusivity.

Asked what it can do to address these issues, he says: “They have to want to do something. I think we have to cross that line before the conversation starts on what they can actually do.

“I think U.S. Soccer has been the main culprit in letting the system evolve into what it is today.

“Everyone is in it for what seems the profit motive rather than to develop good soccer players.”

When contacted for comment, U.S. Soccer rejected Lowery's criticism but did not provide any examples of how the organization is actively tackling issues that young ethnic minorites face with the existing system prior to publication.

Although U.S. Soccer is known to run a scholarship program for its Girls' Development Academy and encourages clubs to subsidize costs for youth players from low-income families, Landau added: "It’s bigger than any one club. It’s the way the system has evolved, it’s the way the business of soccer in this country has evolved."

A visit to Landau’s DC Scores a few years ago from some Manchester United coaches emphasized their point. As they watched on as those part of the program trained, they were taken aback by the talent and, in stark contrast, the lack of opportunity they had been given.

“They were stunned,” Landau explains. “They were working with the kids in the city and they were stunned that none of these kids were playing organized youth soccer.

“Their point was in England or in other places, they would be sent to find kids like this, and nobody is coming to find these kids.

“The lack of community outreach and gap-bridging that is done, just based on the way the system has evolved, is another issue too.”

Open Goal Project

Open Goal Project

While in countries like England coaches spend a lot of time around the non-professional game looking for new talent, the attitude in the US is to focus on those already in the system.

"The ultimate belief behind everything is that U.S. Soccer is missing out on the best players, or some of the best players, by neglecting kids in urban areas, by neglecting minorities,” Lowery says.

“To just totally throw a blanket over everyone who can’t afford it and push them out of the equation, I think there’s a solid argument that we’re missing a lot of talent.”

U.S Soccer argued that "this is not a blame you put on one organization" and can rightly point to the U.S. men's national team, whose Gold Cup 2019 roster is incredibly diverse - over half the team are ethnic minorites.

Dunn, one of the USWNT’s four players on their Women’s World Cup 2019 roster with an ethnic minority background, commented on diversity in June.

"I am seeing so much more diversity and I think that's really all I hope for, year-in, year-out,” the 26-year-old said.

“It's always progressing in the right direction and especially being a woman of color I always root so much for the black girls that are doing well and I'm always rooting for diversity in this sport continuing to grow.

“I've been seeing it so I'm quite happy with it."

Lowery, however, argues otherwise: "I was playing club soccer here in the 1990s and my club team was more diverse here in D.C. than the team I was coaching.

“All the teams I played for were more diverse than the team I was coaching and the teams within the club. I haven’t seen [an increase in diversity]. I’ve actually seen the reverse.

"There’s not one Latina on the [USWNT]. In the entire population of the United States, which has many Latina, it makes absolutely no sense that there’s no one on that roster.

“That’s just not more representative.”

Lowery and Landau know full well what sort of talent professional soccer teams are missing out on by neglecting lower-income communities.

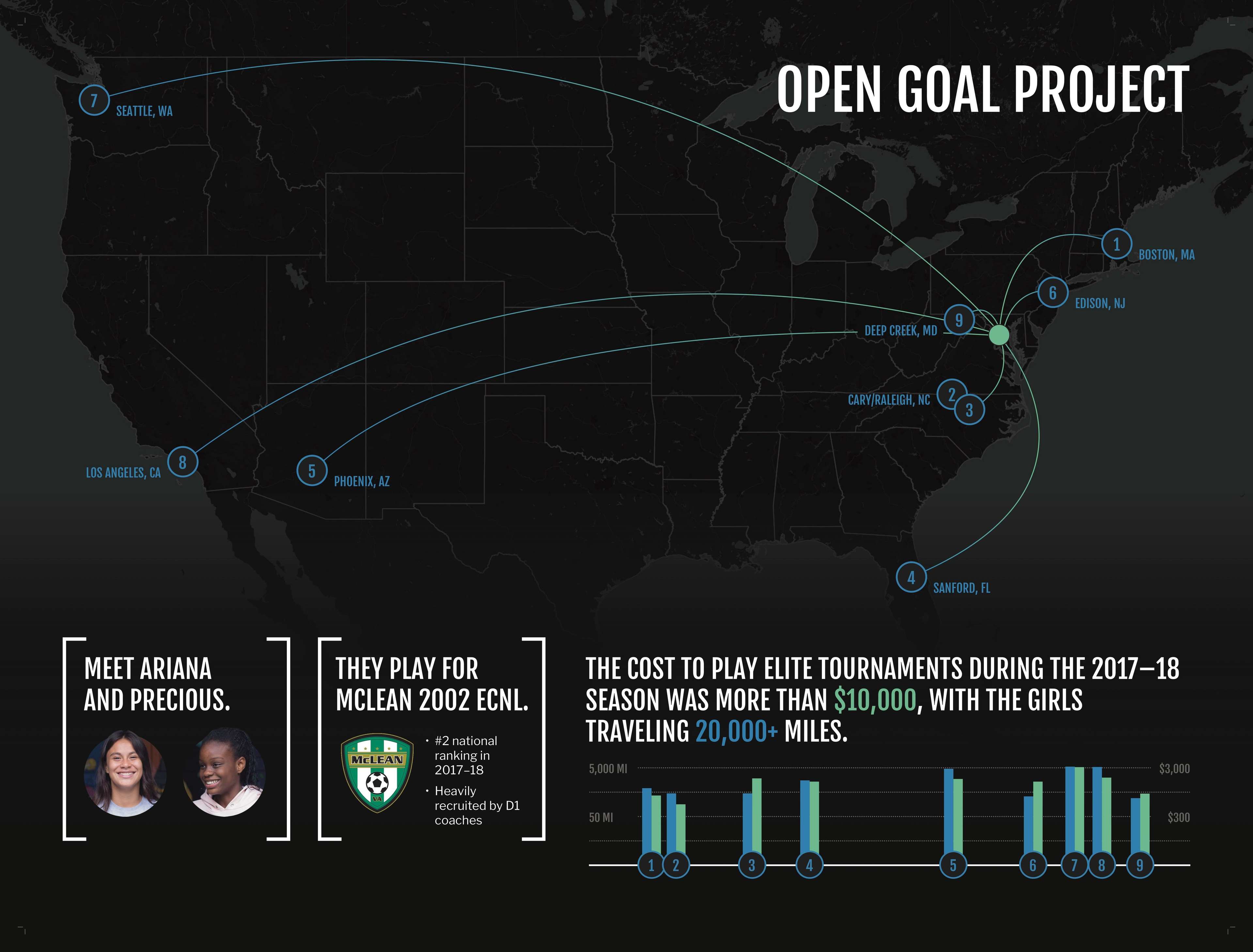

Ariana (16) and Precious (15) are two girls to be aided by Open Goal Project, playing for the McLean, a team ranked second in the U.S. in their age group last year when the pair were there.

Both players were picked up by Lowery when playing recreational soccer and worked into the system by his contacts, while being funded by Open Goal Project's programme.

Despite no previous involvement, and Precious playing a year up from her age group, they shone for the team and became two of their star players - something that may not have been possible without Open Goal Project.

Their success only further highlights Lowery's stance that it's "critical" for soccer in the United States to be more accessible to ethnic minorities.

"If not, I think we’ll suffer over the next 10 or 20 years," he says. "We’re essentially cutting out half of the population and not giving them access.

"We’re taking the best players from one half of the population. If you open it up to everybody, imagine."

France, like the U.S., is a country rich with immigrants from diverse backgrounds. Unlike the U.S., that diversity shines through in their women's team thanks to support from the likes of French coaching legend Aime Jacquet.

Jacquet helped to push the France football federation to open Clairefontaine - the most renowned youth academy in the country - to girls. The result is a women's national team truly representative of the diverse nation.

"Diversity is really a positive in a country or even a team," Paris Saint-Germain and Les Bleues forward Kadidiatou Diani told the New York Times. "Maybe it’s the reason why France won the [men's] World Cup [in 2018], this multiculturalism. It represents France."

Former U.S national team coach Bob Bradley, who's worked in France, agrees. "France has football history, France has diversity and multiculturalism," he said. "And all that amounts to is talent. It has interesting, exciting talent."

So do the reigning world champions, a formidable team with extraordinary players, but it's impossible to argue it represents the United States where 4 in 10 people aren't white.

To learn more about what Amir and Simon do, and how you can help fund their programme, visit https://www.opengoalproject.org/