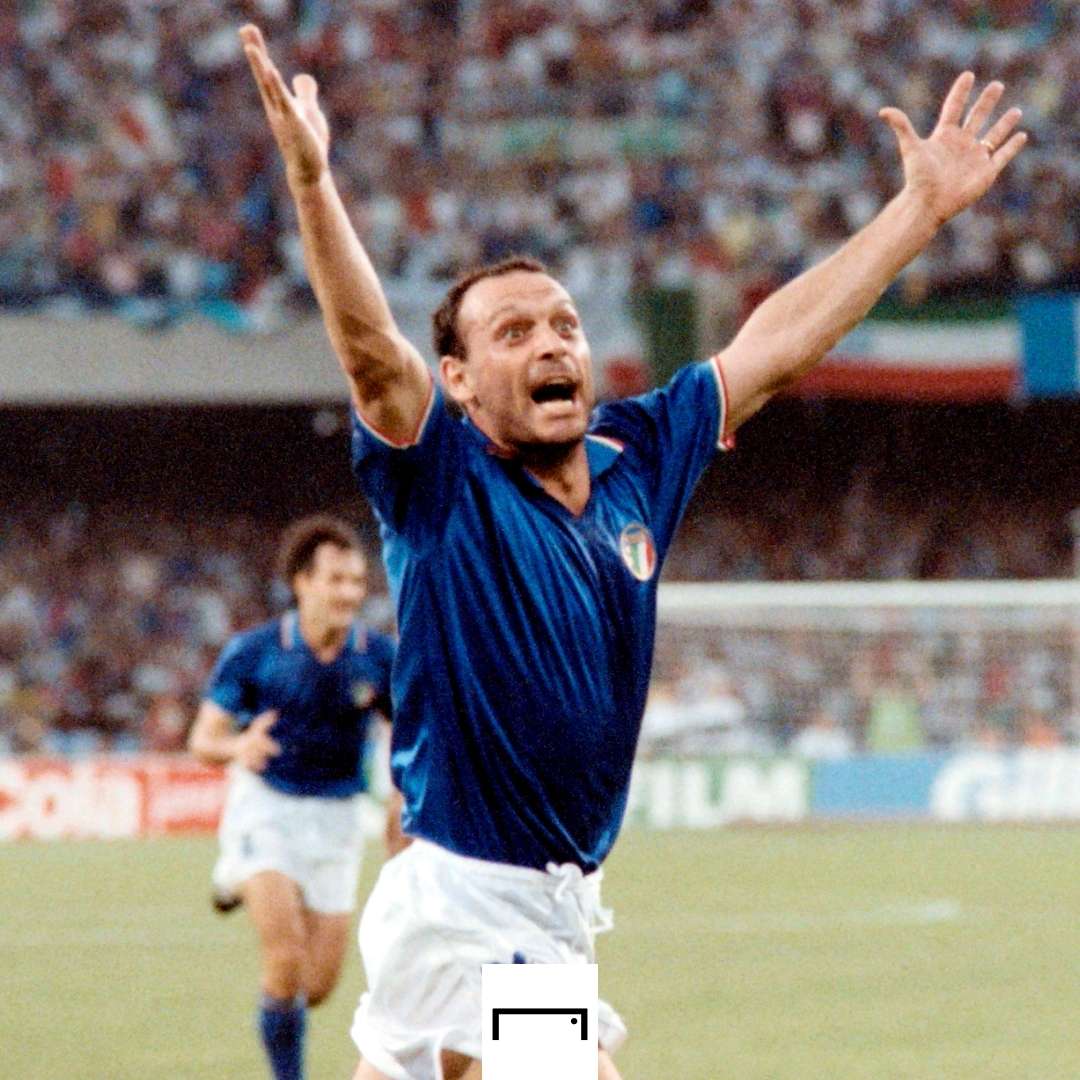

West Germany won the 1990 World Cup. But the tournament belonged to Salvator Schillaci.

"I feel like I'm sleeping," he told reporters after opening the scoring in Italy's last-16 win over Uruguay. "So, don't wake me up! Let me enjoy this dream!"

Schillaci's state of disbelief was understandable. This was a young man from a poor neighbourhood in Palermo who had spent the majority of his career playing in Italy's lower league with Messina.

He'd only made his first appearance in Serie A the previous August, and his international debut just three months before the World Cup began.

Just making the squad was an achievement in itself. He freely admitted that he would have been happy just sitting on the bench for the entire tournament.

Next Match

After all, Schillaci was arguably Italy's sixth-choice attacker, behind Gianluca Vialli, Andrea Carnevale, Aldo Serena, Roberto Mancini and Roberto Baggio in the pecking order.

However, he was a man in form, having hit 21 goals in all competitions during his first season at Juventus, whom he had joined the previous summer on the back of a prolific campaign at Messina under Zdenek Zeman.

Only Marco van Basten (19), Baggio (17) and Diego Maradona (16) had struck more times than Schillaci (15) in Serie A in 1989-90.

However, as Schillaci himself subsequently admitted, "not even a madman could ever have imagined what was going to happen to me."

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOAL"There are periods in the life of a football player when you can do anything," Schillaci added. "For me, this state of grace coincided with the World Cup. Somebody up there decided that I should become the hero of Italia 90."

It's easy to understand why Schillaci still feels that there may have been an element of divine intervention in his miraculous rise to stardom, but Azeglio Vicini arguably played a greater role.

The Italy coach had already sprung a surprise when he included Schillaci in his World Cup squad, after just one previous appearance, in a friendly with Switzerland, but his decision to bring him off the bench in the Azzurri's tournament-opener, against Austria, stunned many.

However, with the hosts struggling to break down a well-drilled side, a desperate Vicini decided to replace Carnevale with Schillaci rather than Baggio.

Schillaci only had 15 minutes to make an impact; he needed only three, getting his head on the end of a wonderful cross from Vialli.

"Everything went mad," Schillacci later admitted to Four Four Two.

Despite his match-winner, he found himself back on the bench for Italy's next game, a 1-0 victory over USA, but he again replaced the struggling Carnevale, this time just six minutes after half-time.

It was clear that Schillaci was edging closer to a starting spot and it arrived in the final group game, against Czechoslovakia.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALHe netted just nine minutes in, and never looked back. He was brimming with belief, as so perfectly illustrated by the thumping strike which broke the deadlock against Uruguay.

His match-winner against Republic of Ireland, meanwhile, underlined that everything just seemed to just be falling his way, with Schillaci left with an open goal after Pat Bonner had spilled a shot from Roberto Donadoni.

If ever a man was in the right place at the right time, it was Schillaci at Italia 90. Indeed, he arrived right on cue again to put Italy ahead in the semi-final.

And it appeared as if Schillaci's scuffed, close-range rebound would be enough to see off a desperately pragmatic Argentina side, given the Azzurri had yet to concede a single goal in the tournament.

But Claudio Caniggia levelled from a corner – Walter Zenga would be cruelly castigated for failing to deal with the cross – and the Albiceleste prevailed in a penalty shootout.

Schillaci was devastated, afterwards spending two hours in the dressing room crying and smoking cigarettes.

He would end up winning both the Golden Boot, thanks to a penalty in the third-place play-off defeat of England, and the Golden Ball.

But the Sicilian admitted that he would have gladly given up both prestigious prizes to have lifted the World Cup with his team-mates.

Sadly for Schillaci, he would never hit such heights on a football field again.

Indeed, he would score just one more goal for Italy, while he failed to build on his promising debut season at Juve and was eventually sold to Inter, where he fared even worse, with injuries and personal problems taking their toll.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALSchillaci himself admitted that he struggled to deal with the fame which followed his heroics at World Cup 90, and his late-career move to Japan was an attempt to escape the constant media scrutiny.

"At some point in my life, I turned off the sports spotlight," he explained to Gioco Pulito. "I closed myself off and I didn't want to do anything anymore because basically I have a very shy character.

"Then, one day, I looked in the mirror and realised that someone like me, who has done something in life, who has also written a bit of football history, shouldn't have closed himself off."

So, Schillaci began to embrace his life as a celebrity, making numerous appearances on television, as well as writing an autobiography in which he addressed the territorialism he endured during his lowest moments after the World Cup.

He also founded a sports centre in his native Palermo which he hopes will enable other Sicilians to follow in his footsteps.

Indeed, when Schillaci looks back on his football career, there is no bitter regret, only gratitude at having been lucky enough to live his dream for an entire summer.

"Even when I go abroad," he revealed, "thanks to the World Cup, people know who I am."

Toto Schillaci, the hero of Italia 90.