“It’s just beyond brutal,” Dawn Astle says, as she reflects on the dreadfulness of her father Jeff’s dementia, which killed him in January 2002.

“You could read 1,000 books and listen to 1,000 people, but unless you’re living with it 24-7 like my mum was, at the age of 50, I don’t think people can fully understand.”

Astle’s gut-wrenching personal experience – which included watching her dad choke to death – has fuelled her relentless campaign to prove heading can cause neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia.

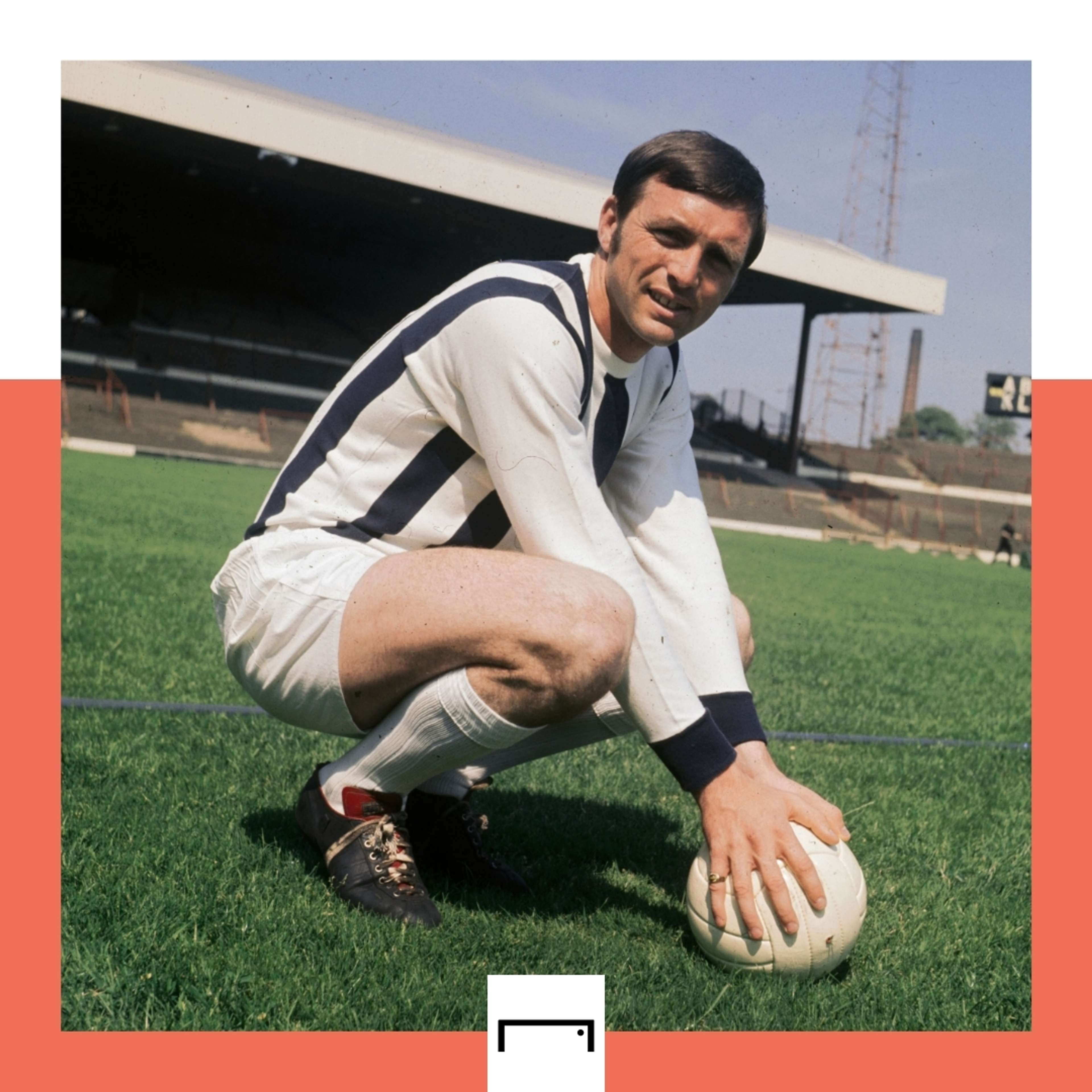

In November 2002, the former West Brom and England striker became the first British footballer to have been ruled by an inquest to have died due to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a type of dementia.

In the case of Astle, who was just 59 when he died, the low-level brain trauma was proved to have developed from the repeated heading of footballs.

Now, 20 years on from her father’s death, Astle’s daughter tells GOAL why football’s attempts to mitigate the potentially deadly effects of heading have not gone far enough.

She is desperate to protect other ex-footballers from the horrendous fate endured by her dad, who enjoys legendary status at West Brom after scoring 174 goals in 361 games.

“This isn’t a broken leg or a metatarsal injury or arthritis later in life,” Astle says. “This is catastrophic brain damage that is going to kill you.

"We have no cure, so football needs to get a grip and start putting things in place to protect players.”

Football and former footballers owe a huge debt to the indomitable Astle.

Getty

GettyThrough the Jeff Astle Foundation charity, she has supported about 200 families of ex-players living with dementia.

In February, she agreed to lead a dedicated dementia department in the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) as part of the union’s drive to ensure support for former players with neurodegenerative diseases is “a top priority”.

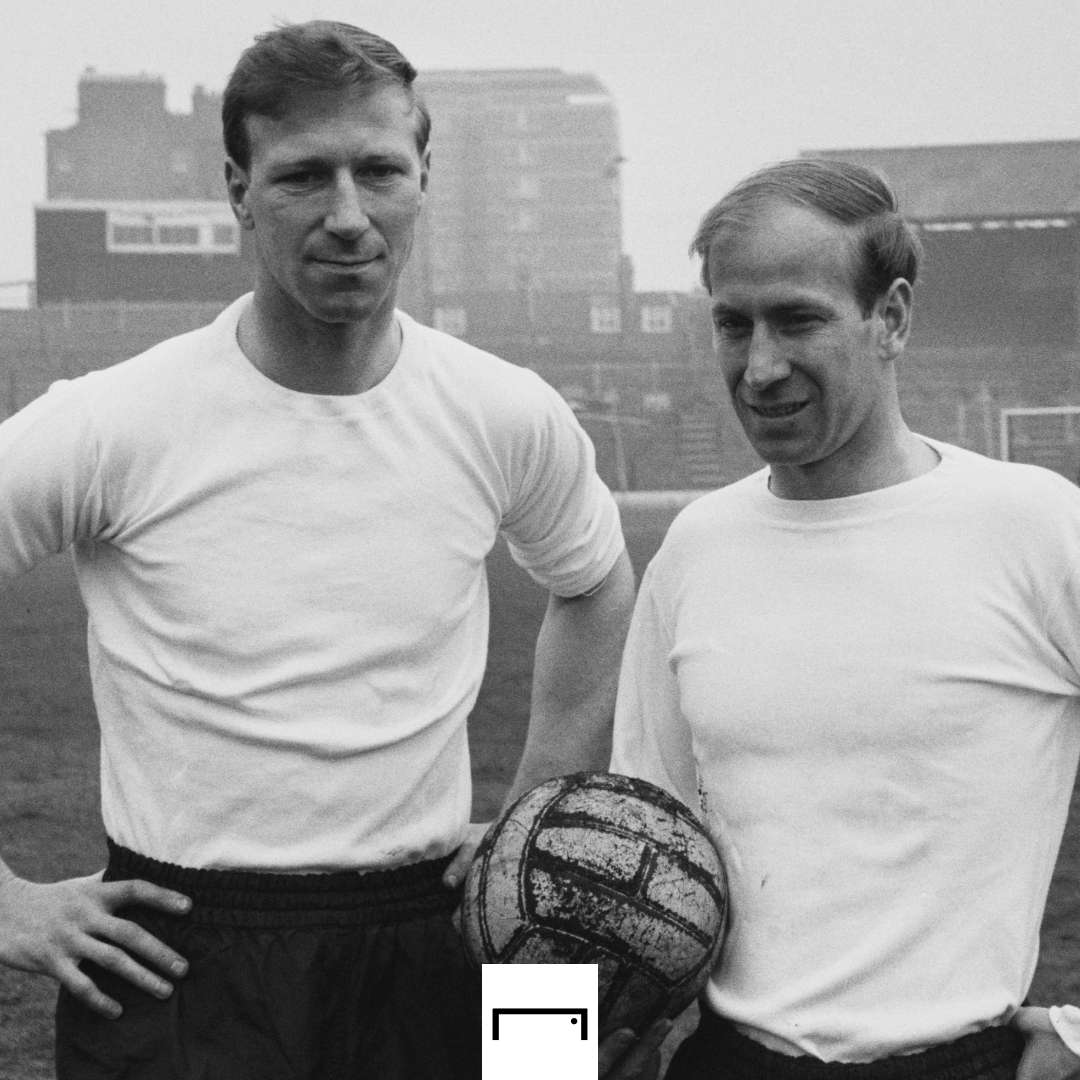

Five of England’s 1966 World Cup-winning team — Ray Wilson, Martin Peters, Nobby Stiles, Sir Bobby Charlton and Sir Jack Charlton — have all suffered from dementia since Jeff Astle’s death.

Countless other footballers of lesser renown have also been afflicted by the terrible condition.

In the landmark case of Astle, who won five caps for England, there was irrefutable and appalling proof about the cause of his death.

“The trauma was right throughout his brain, right throughout every slice as such and from that, they can say it’s from something that’s been impacted on to the head over many years,” his daughter says.

Given the shocking state of Astle’s damaged brain, it is unfathomable how football did not take immediate and robust action.

In 2014, the Justice for Jeff campaign was launched, calling for an independent inquiry into a possible link between degenerative brain disease and heading footballs.

But despite Astle meeting several Football Association officials to push for answers, nothing of substance was done.

Until 2017, that was.

The FA and the PFA appointed the University of Glasgow’s consultant neuropathologist Dr Willie Stewart to lead an independent research study into the incidence of degenerative neurocognitive disease in ex-professional footballers.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALThe FIELD (Football’s InfluencE on Lifelong health and Dementia risk) study’s findings in 2019 proved a seismic moment in football’s escalating dementia crisis.

They showed that professional footballers were three-and-a-half times more likely to die from neurodegenerative disease than members of the general population.

“We’ve always believed that heading the ball was the problem,” Astle says.

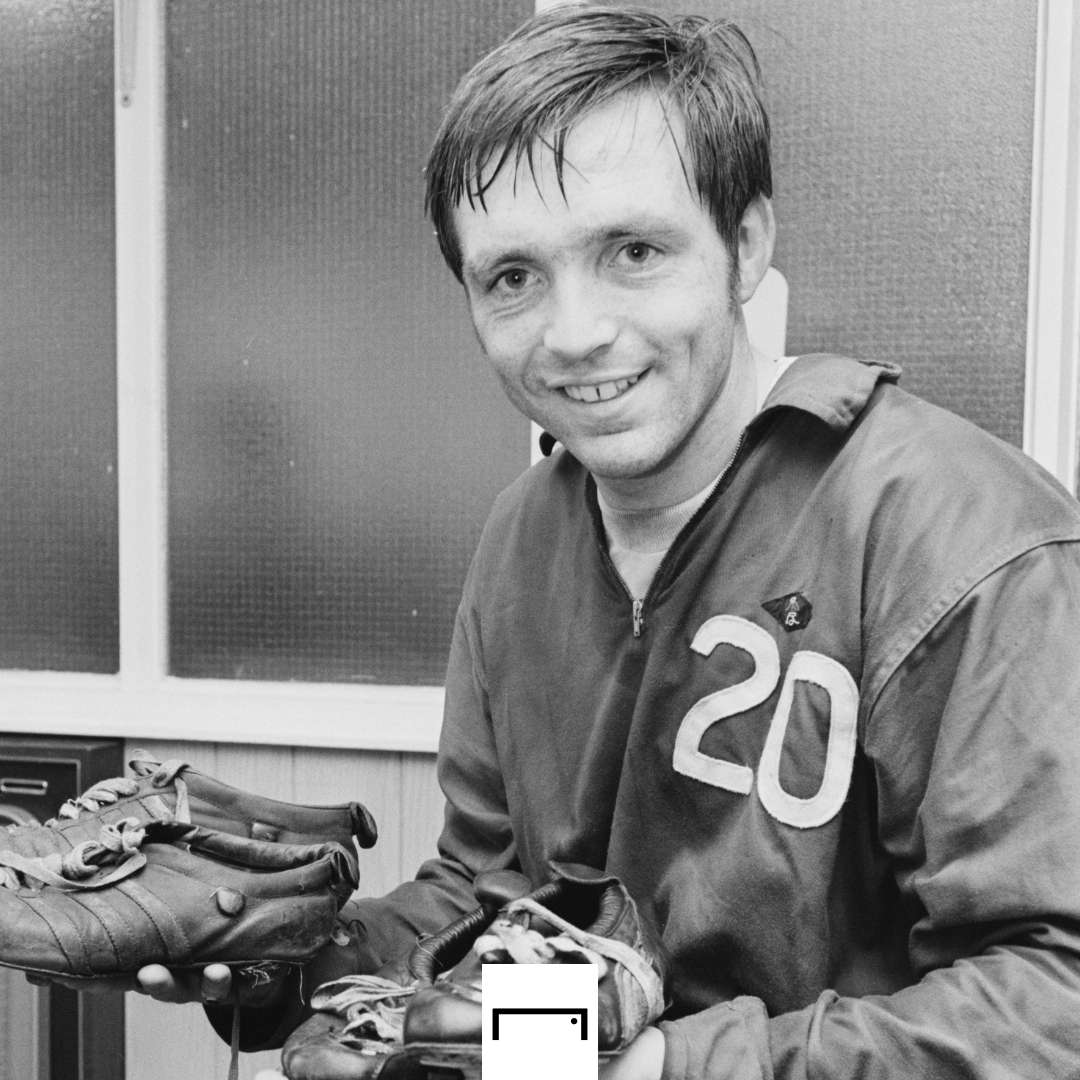

Astle’s assertion is strengthened by the story of Peter Bonetti, the former Chelsea and England goalkeeper, who died in April 2020 after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2011.

Bonetti’s wife Kay told Astle that the only time her husband “didn’t head a football was 3 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon because he used to head medicine balls during the week to strengthen his neck muscles.”

Such old-school practices were thankfully outmoded long ago and football has — after years of inertia — started to tackle the grave dangers of repeated heading.

In 2021, the Premier League launched a study involving Manchester City and Liverpool academy and women’s players wearing mouthguards embedded with microchips in training sessions to help monitor the impact of headers as part of research into brain injuries,

The mouthguards, which were already used in rugby union and rugby league, collected and sent data to coaching and medical staff in real time to show how heading the ball affects the brain.

Astle says: “From that, the FA and the Premier League have now put a limit of 10 on high-force headers a professional footballer can do in a week.

“That in itself shows us the damage that must be imparted on to the brain when you head a ball if sport itself is saying you can only do 10 high-force headers a week. That’s frightening. I was literally shocked when I heard it.

“What the sporting authorities have been clinging on to over the years is that there’s no causal link [between heading and dementia].

Getty

Getty"But when I speak to the experts, we may never find a causal link, or at best it may be another 40, 50, 60, 70 years.

“How it’s explained to me is the time between what they call the exposure, the heading, to the outcome, which is dementia — two decades after my dad retired.

“But if we look at all the evidence we have in front of us now, on the balance of probability it’s heading that’s the problem, so sport has to address that.

“There needs to be a proper education programme for the players so they know about the risks.”

Astle is vigorously opposed to another measure introduced by the Premier League — concussion substitutes.

The concussion substitute law allows each team to make two permanent concussion substitutes if players have head injuries, assessed by qualified medics.

If a player shows no clear signs of concussion they will be allowed to continue, but will be continually monitored by medics on the sidelines.

Astle says: “Every other sport in the world dealing with this goes for temporary concussion substitutes. Football, for whatever reason, has gone with permanent ones.

“But the problem is they’re not working. Week after week, we’re seeing players being assessed on the field of play during the game, only for them to be replaced as the game goes on.”

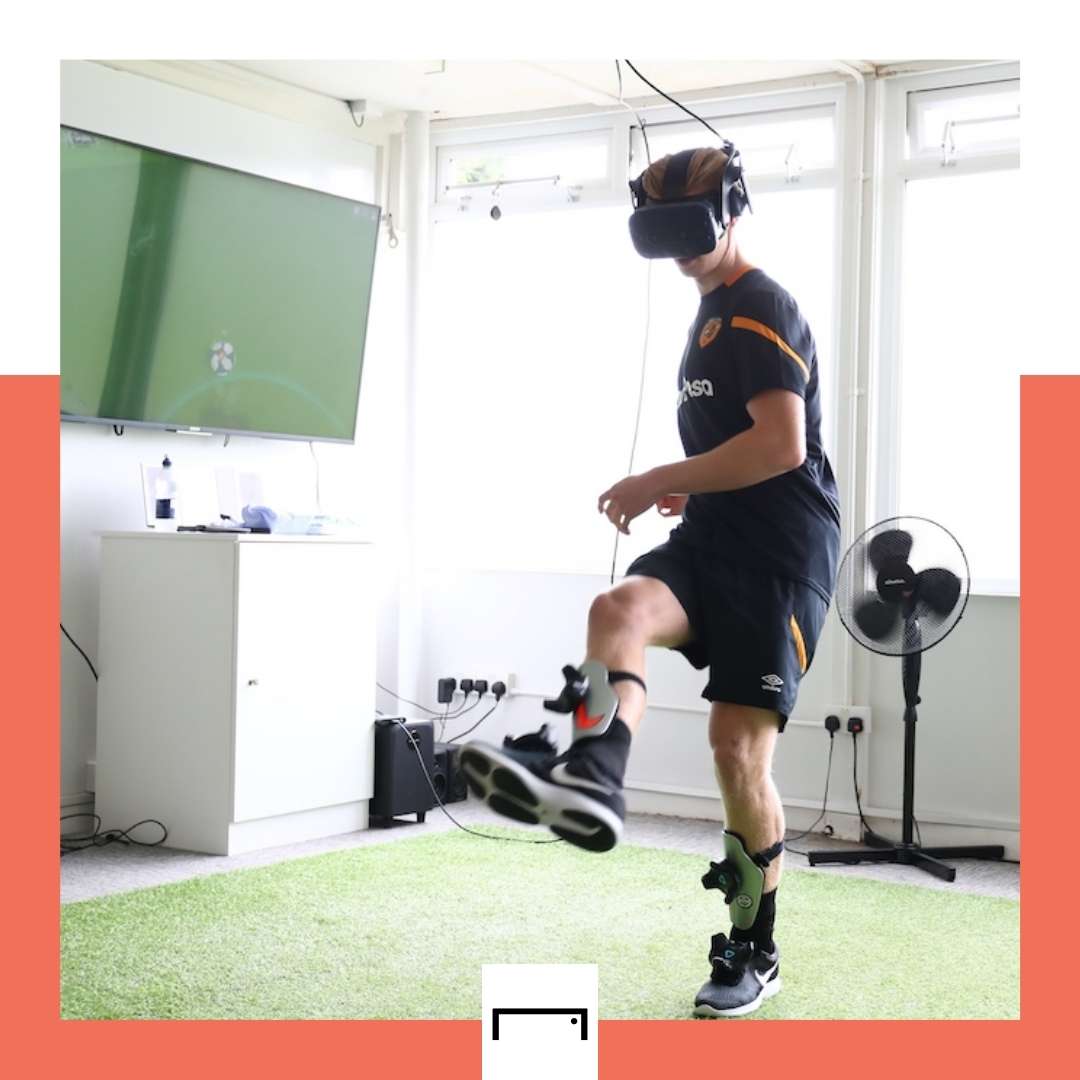

As reported by GOAL, scientists at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute of Sport are trialling Player 22, which helps to train footballers to head a ball without exposing them to the potential dangers of doing so.

REZZIL

REZZILBut should heading be outlawed altogether as it has been with children under the age of 12 in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland?

Astle says of such a drastic move, which GOAL backed in 2017: “It’s a part of the game that’s killing people.

"I do think there will come a time, in 70-80 years when I’m dead and gone, when people will be sitting watching football saying: ‘Did you know, 70 years ago they used to head it? How stupid’s that? They found out it’s killing all these players.’

“Will we ever find a causal link because as I said, the time between the exposure and the outcome is decades?

"I don’t know; I’m not an expert or a scientist. But how can you justify something we know can be a killer?”

How would she convey the devastating impact of her dad’s dementia on both him and his family to football’s authorities?

It is a heartbreaking story she has recounted many times before, but one which will never lose its visceral impact.

“I say it all the time that everything football gave to him, football gave away,” she says.

“You lose a little part of them every day and you’re so helpless because there’s nothing you can do and there is lots of frustration, tears, overwhelming sadness seeing pieces of him stripped away daily, until all that remains is the physical shell of him.

"He couldn’t speak and do the most basic of everyday things for himself.

“As a family, we held his hand and guided him through his daily life and all the futility, despair and pain.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOAL"There were glimpses of joy and brief flickers that passed his eye and we thought there was a split-second of recognition, which carried you through but broke your heart in equal measure.

“When he died, he was with me and my sisters, our partners and our children, and mum — and he choked to death in front of us all. I’d just say to [the footballing authorities]: ‘Just think of that for one minute.’

“It’s something you never forget and it haunts me every day of my life. It was just horrific.

“That’s why we do what we do because we don’t want any player to go through what my dad went through and no other family to go through what we went through.”

Astle concludes by urging former footballers to agree to donate their brains.

Organ donation was something she says her dad was passionate about aside from football, cricket and horse racing.

It has now proved to be his lasting legacy.

“Brain donation is the most valuable gift for future generations of footballers,” Astle says.

“My dad’s brain is now speaking for the living and giving us the gift of knowing — and because of that for today’s generation and for future generations, it’ll be safer.

"That’s not down to me, or my family or the Jeff Astle Foundation, that’s because of my dad — and that’ll be his legacy for always.”

For more information on the Jeff Astle Foundation, click HERE