It is one of football's most daring, eye-catching, all-or-nothing moves.

Fail to pull off a rabona, and endless ridicule – not to mention a rather embarrassing and painful fall – awaits. Get it right though and, as Erik Lamela knows better than most, mythical status is only a short step away.

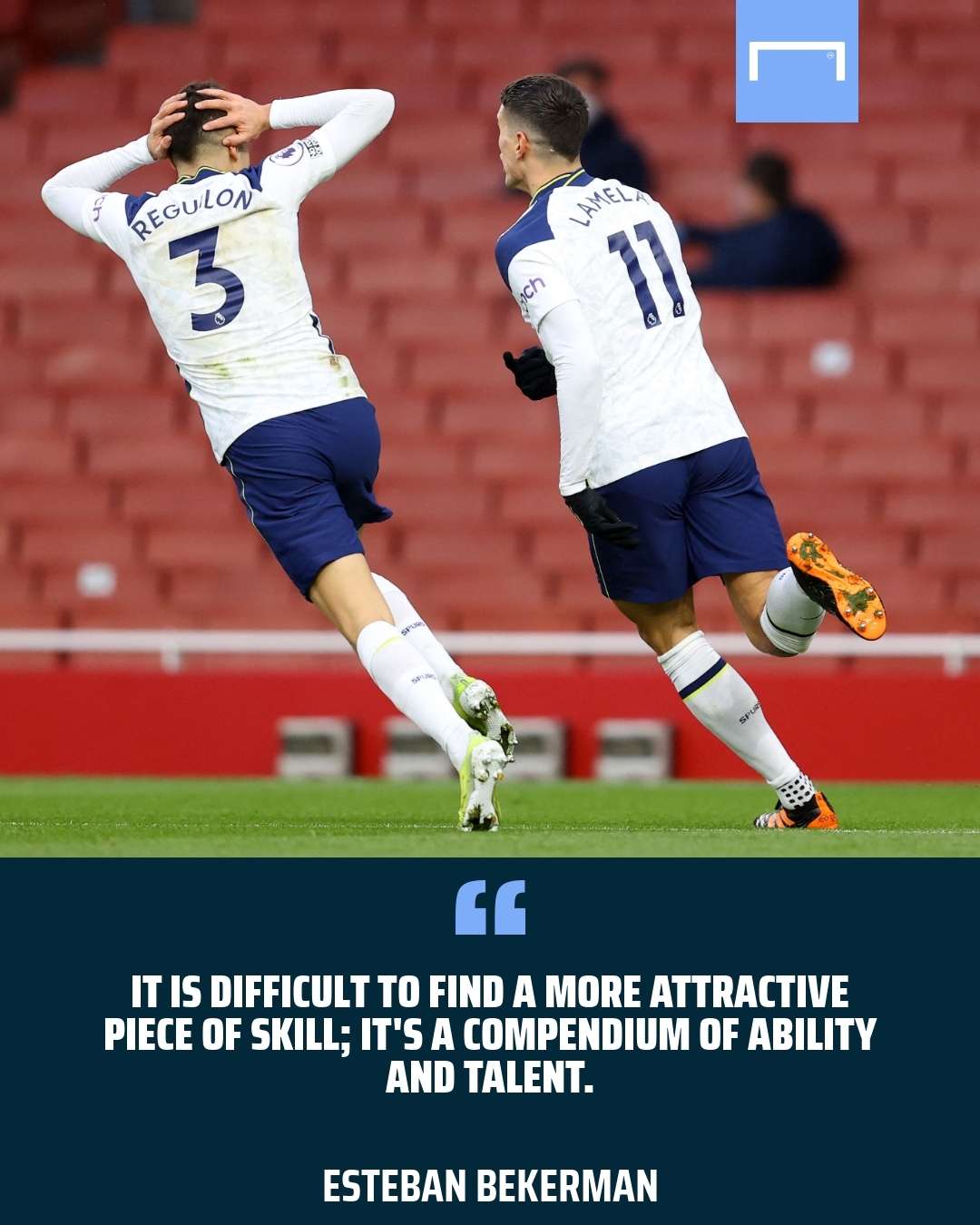

Tottenham's Argentine star hit the headlines in an otherwise disappointing north London derby for the visitors as he opened the scoring with incredible poise and ability, leaving Bernd Leno dumbfounded in the Gunners net.

Arsenal later recovered and ran out 2-1 winners, with Lamela making an early exit after seeing red, but the image of his left foot, wrapped around the back of his right shin and propelling the ball towards goal, will endure far longer in the memory.

In doing so, he continued a proud Argentine tradition which stretches back almost to the final years of World War II, if not even earlier.

The first rabona goal for which reliable records exist dates back to September 19, 1948, some 60km from Lamela's Buenos Aires birthplace in the city of La Plata.

There, Estudiantes' 24-year-old striker Ricardo Infante used the technique 25 metres from goal to net his side's third of a 3-0 victory over Rosario Central, writing his own name into the history books in the process.

“[Julio] Gagliardo's shot hit the left post and the ball sprang back the other way,” the late striker, who is the sixth-highest scorer in Argentine league history with 217 goals, recalled to Clarin in 1998.

“It bobbled a little and, as the field – uneven, with patches of grass – helped out, I just had to wedge my right foot behind my left leg. The effect was incredible. I never imagined I'd put it there, right in the left top corner.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Such was the impact of his strike that the referee and even the defeated Central goalkeeper approached to congratulate him.

“[Infante's goal] was the first to receive that name,” Argentine football historian and owner of the Entre Tiempos memorabilia store in Buenos Aires Esteban Bekerman tells Goal. “There were most likely similar goals beforehand, but it was the first to be called a 'rabona'.

“Infante was an extremely well-known player from the 1940s and 50s, he emerged as one of the stars of the so-called golden generation of Argentine football in the 40s, possibly the greatest of all time.

“It was an age in which the best Argentine players were not tempted to go abroad to play, obviously because of the war in Europe but also because they were very well-off here in Argentina, the country was doing well economically, so there was no need to leave.”

No film footage exists of Infante's ground-breaking feat, leaving only the 20,000 fans inside Estudiantes' old ground in La Plata as witnesses.

“Explaining it is neither easy or difficult; you would have to have seen it,” the report in local newspaper El Dia offered by way of description.

A cartoon accompanying the article featured dumbfounded fans attempting to make sense of what they had seen: “How did he do it? What did he do? This needs a name..." while the player himself suggests, "Just call it Infante's goal!”

Lying by his crossed feet, meanwhile, the photographer begs Infante: “Don't move your legs! This photo will be in all the dictionaries!”

A name worthy of the move was forthcoming.

“A title came out in an Argentine newspaper, since Infante was still very young, that said he 'did a rabona'. Doing a rabona meant to skip school classes,” Bekerman explains.

El Dia La Plata

El Dia La Plata

Venerable Argentine magazine El Grafico has long been credited with the invention of the name, a classic football pun bringing together both the surname Infante (Child) and Estudiantes (Student) for added effect, but this seems to be an urban legend.

By all accounts the phrase does not appear in the two following editions, although on October 7 legendary columnist Borocoto does reference the goal in its pages, stating: 'This was not a goal, it was a poem, a symphony... another Beethoven!'

The true origin may well remain unknown. "Perhaps it was a local paper in La Plata and it then got associated with El Grafico," Bekerman suggests.

While there was an attempt some 30 years later in Italy to attribute the move to Ascoli's Giovanni Roccatelli, FIFA in 2014 publicly recognised Infante as the 'inventor' of the rabona - still known in its original Argentine slang form across the globe.

Indeed, while it has long since gone global, the daring and unorthodox execution of the rabona, not to mention its usefulness on less than ideal playing surfaces, seem to suggest its origins as a quintessential product of the potrero, patches of semi-urban wasteland on the peripheries of Argentina's biggest cities which honed the talents of budding stars like Diego Maradona.

“It's THE product of a superior technical ability,” Bekerman agrees. “It is difficult to find a more attractive piece of skill, it's a compendium of ability and talent.”

Lamela, who already boasted a similar goal to his name while playing for Spurs against Asteras Tripolis in the 2014 Europa League, thus is the latest in a long tradition of stars to hold the trick in their repertoire.

Perhaps the finest exponent of the rabona was Claudio Borghi, Maradona's heir to the No.10 shirt at Argentinos Juniors and his team-mate in the 1986 World Cup, and known for his exquisite technique on the ball. “For me, it was a case of turning a defect to my advantage, as I never had a good left foot,” Borghi told FIFA.

“The beauty of the trick is that opponents don’t see it coming so you can put the ball pretty much where you want. Like anything unpredictable, it causes problems for opponents.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Maradona himself was also proficient with the move, as with almost anything related to the game. Angel Di Maria often utilises it in his passes, invariably catching defences off-guard. Even defender Marcos Rojo has been known to stun crowds every now and then with a crooked flick of his left foot.

Curiously, one Argentine star who shuns the rabona is Lionel Messi, who tends to favour a more direct route to goal around or through defenders when the ball is at his feet.

Is the rabona a valid part of the footballer's toolkit, then, or a crowd-pleasing gimmick?

In 2019 Boca full-back Julio Buffarini tried it in a cross whilst leading 3-0 against former club San Lorenzo, provoking the wrath of his ex-team-mates. Having sparked an on-field brawl, earning a yellow card for his troubles, Buffarini subsequently apologised to his opponents, admitting the rabona may have been "unnecessary", even if it was far from the first time he had tried it out.

Like Borghi, Lamela maintains that the move comes naturally to him, telling reporters after his strike against Asteras: “I wasn’t thinking about doing something like that, I just wanted to score and it was the most effective, comfortable way of making it happen.”

Bekerman is inclined to agree. “Generally the players that use this movement do so because they have the necessary technique to pull it off, because not any old player can do it, you have to have a lot of ability,” he points out.

“If you don't, you run the risk of being made to look a fool, ending up in a heap on the ground, facing the crowd's derision. I don't think it's something you can do just to get the crowd going, you have to be a player who really knows what he's going and who has the talent to make it work.”

Whatever the intention behind it, there are few more stunning sights in football than when a player like Lamela sends a rabona strike past a flailing goalkeeper.

It may not have sufficed for Spurs to win the north London derby, but the goal will go down in history – and might inspire the next generation of talents, just as the exploits of Infante and later Borghi and Maradona had such an impact on the likes of Lamela as they were learning their trade as kids in Buenos Aires.