When Giorgio Chiellini appeared for his post-match interview, the camera crew gave him a stool to sit on.

He'd only played six minutes but he looked like he needed it. Chiellini was, by his own admission, "destroyed".

Italy had just failed to qualify for a second consecutive World Cup for the first time in the nation's history, their hopes of playing in Qatar 2022 ended by a humiliating 1-0 loss at home to North Macedonia.

"There's just a great disappointment but we need to start over," he told RAI. "But right now it's difficult to even talk about it. There's going to be a great void."

How had this happened, though? How had the reigning European champions failed to qualify for Qatar, eliminated by the 67th-ranked team in the world?

Chiellini struggled to find the right words, admitting, "It's inexplicable."

There were several reasons, though, chief among them Italy's inability to score goals.

Did they deserve to lose on the night? Hardly; they dominated possession and had 32 shots to North Macedonia's four – the expected goals [xG] ratio was 2.43 to 0.16 in Italy's favour yet Aleksandar Trajkovski decided the play-off semi-final with a 92nd-minute winner from distance.

It was cruel but, as Chiellini conceded, you always end up paying for mistakes at the highest level, and the Azzurri's attack ran up quite the bill in Palermo.

Domenico Berardi missed what was essentially an open goal, presented to him by an awful error from North Macedonia goalkeeper Stole Dimitrievski.

At least Berardi had been one of Italy's brighter players, though. His fellow forwards had performed pathetically.

Ciro Immobile may be a Lazio legend but he has never managed to transfer his prolific record at club level to the international arena and some have already suggested that he never play for the Azzurri again.

The 32-year-old certainly looked too slow and too cumbersome for the highest level.

Shortly before his 77th-minute withdrawal, he set off after an inviting through-ball and yet somehow managed to end up further away from the goal than when he'd started his run.

By that stage, the diminutive Lorenzo Insigne, who incredibly seemed to shrink in stature on the night, had already been taken off after a painfully ineffective performance.

There remains, of course, a wonderful sense of togetherness within Roberto Mancini's squad; it was this unity, combined with the coach's atypically adventurous approach, which enabled the Azzurri to triumph at Euro 2020.

So, it was no surprise to hear so many players attempt to deflect the focus away from the misfiring forwards.

Jorginho, for example, was quick to acknowledge that if he'd scored either of his penalties in the home-and-away draws with Switzerland in the group stage, Italy wouldn't have even ended up in the play-offs.

"I do still think about those misses," the teary-eyed midfielder told RAI. "It will haunt me for the rest of my life."

Italy's World Cup elimination, though, wasn't about one particular player; this was a collective failure, one that extends well beyond what happened in Palermo.

Chiellini pointed out that the players paid the price for mistakes made in previous matches, but they're also counting the cost of years of mismanagement at the very highest level.

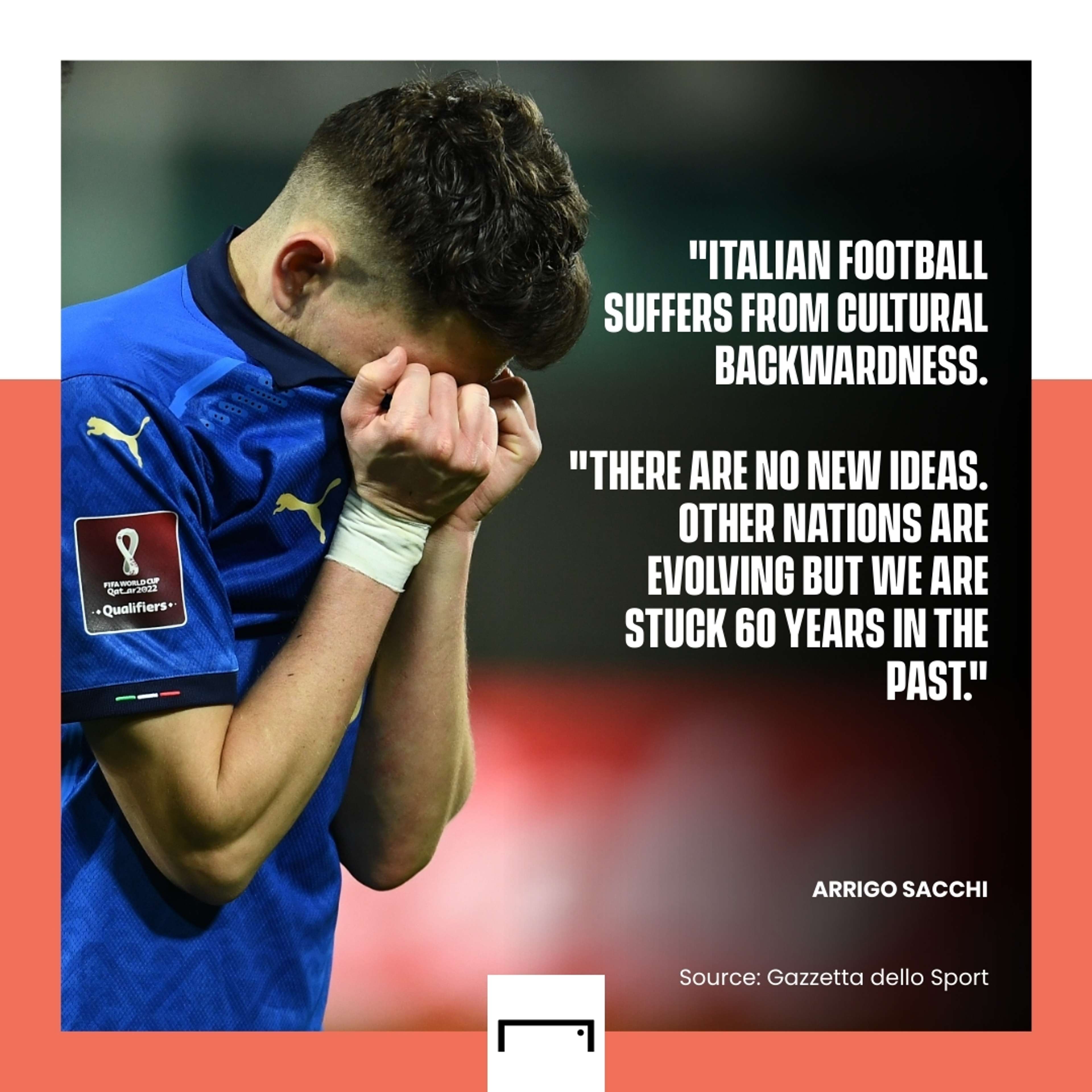

"We're reaping what we sowed," as coaching legend Arrigo Sacchi told the Gazzetta dello Sport. "We talk a lot, but you don't resolve problems with only words."

Action is clearly required, as there is clearly something wrong with the production line.

This is a nation that once brought Alessando Del Piero, Roberto Baggio, Filippo Inzaghi, Christian Vieri and Enrico Chiesa to the same World Cup.

On Thursday night, in their desperate search for a goal, they brought the recently naturalised Joao Pedro off the bench for his international debut. The Cagliari striker hadn't even scored in Serie A for two months!

There is no more damning indictment of the Italian game, which has been underperforming at both club and international level for more than a decade.

Remember, it's not just that they haven't qualified for the past two World Cups; they haven't even made the knockout stage since winning the tournament in 2006, having failed to get out of their group in both 2010 and 2014.

In that context, Italy's Euro 2020 triumph cannot be framed as anything other than a beautiful anomaly, one made all the more unbelievable by Serie A's struggles to remain relevant in continental competition.

No Italian team has won a major European triumph since Jose Mourinho's Inter lifted the Champions League in 2010.

Furthermore, just like last year, Serie A won't even have a single representative in the quarter-finals of the game's premier club cup competition.

Getty

GettyFinancial disparity is often put forward as an excuse for such underperformance.

Italian clubs aren't backed by oil states or boosted by gargantuan TV rights deals like the Premier League – so, the argument goes, how can they possibly compete with the likes of Manchester City and Paris Saint-Germain?

But the failings of the biggest Italian clubs cannot be excused. After all, Atalanta, with their tiny budget but fantastic scouting network, remain Serie A's last Champions League quarter-finalists, in 2020. By contrast, Juve, the tenth-highest revenue earners in Europe, have bowed in the last 16 for the past three years.

The playing field in European football has undoubtedly been skewed by money but, again, the Italian game really only has itself to blame for falling behind.

The golden years are long gone, because of incompetence, corruption, gross financial mismanagement and a devastating lack of foresight, leaving Serie A sides scrambling around trying to make up lost ground by whatever means necessary.

Most top-flight stadia are a disgrace, literally falling apart, yet Italian bureaucracy makes renovation or the construction of a new home almost possible.

It's a turn-off for fans. Go online and you'll actually see heated arguments over the standard of the toilets at the likes of the Stadio Diego Armando Maradona.

Is it any wonder, then, that the grounds are so rarely full? And empty arenas do not make for good television.

Say what you will about the Premier League – and there is plenty to say about the way in which many of its teams make their money – but it was, and still is, masterfully marketed.

Serie A is anything but, with the organisers doing a woeful job of promoting their product.

The league's supposedly English-language Twitter handle has become a figure of ridicule, a microcosm of the Italian game's inability to appeal to a larger audience.

There needs to be a complete change of mindset, from top to bottom, because it's clear that the old ways are no longer working.

Getty

Getty"Italian football suffers from cultural backwardness," Sacchi said. "There are no new ideas. Other nations are evolving but we are stuck 60 years in the past.

"I’ll say it clearly: the least culpable for this situation are the players and the coach. The problem here is institutional."

One of Sacchi's principal gripes is with the amount of foreign players in Serie A academies and it's certainly concerning that, as Italian Football Federation (FIGC) chief Gabriele Gravina pointed out, "only around 30 per cent of youth-team players are Italian".

However, as Gravina acknowledged, that wouldn't be quite so big a problem if the top talents were getting game time in the senior squads, but they're not, with forwards finding it particularly to make the breakthrough at big clubs.

It's been this way for years, though, so it's no wonder that Mancini's matchday squad for North Macedonia didn't contain a single attacker from AC Milan, Juventus or Inter – Serie A's superpowers.

Mancini has been criticised for keeping faith with those that served him so well at the Euros, but that was hardly surprising.

It would have been a bold approach to gamble on younger players who are playing so infrequently in Serie A, given he gets so little time to work with them anyway.

Indeed, it's worth noting that the league rejected Mancini's proposal to postpone the final round of fixtures just before the international break, meaning he was left with just one full day to prepare his players for a World Cup play-off.

There is no better example of the self-destructive nature of the Italian game.

Getty

GettyThe issue was raised afterward the game in Palermo and Gravina said while the lack of preparation "didn't help" and that the top Serie A sides see the national team as a "nuisance", he didn't want to "cause controversy" by discussing the matter any further.

Not for now, at least. But it's clear that a new approach is required; both reform and renewal utterly essential.

And Gravina, who's been at the helm of the FIGC for nearly four years, cannot shirk his responsibility for this catastrophe. He and his organisation have spoken a lot about problems yet done very little to resolve them.

Italy failed to embrace change after the 2017 play-off loss to Sweden; the same mistake cannot be allowed to happen again.

Investment must be made in every sector of the game, and inspiration taken from the way in which France, Germany, Spain and England have all previously overhauled their youth programmes after crushing international disappointment.

However, after such a devastating defeat in Palermo, it was difficult for anyone to look too far ahead, least of all Mancini.

He understandably couldn't quite work out how, in less than a year, he'd gone from the greatest night of his coaching career, to its worst.

Gravina, Chiellini and others urged him to stay on to oversee the rebuilding job, but the coach would only say "The disappointment is too big right now to talk about the future."

Indeed, for now, there is only "a great void". Where a World Cup place should have been.